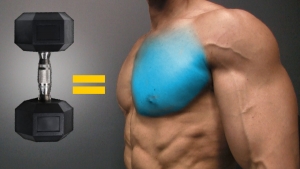

WHY DO dumbbell deadlifts?

The best example is the Dumbbell Deadlift.

It’s looked at as the lightweight cousin of Barbell Deadlifts, but the truth is that Dumbbell Deadlifts are just as effective.

They can build just as much muscle, hit the posterior chain in ways barbells don’t, and even protect your lower back if you’ve struggled with pain while performing Conventional Deadlifts or Sumo Deadlifts.

If you’ve been chasing heavy PRs while your form breaks down and your back pays the price, the transition to Dumbbell Deadlifts might be the smartest move you make.

Let’s break down how to perform Dumbbell Deadlifts with perfect form while avoiding the mistakes that crush progress.

DUMBBELL DEADLIFTS: MUSCLES WORKED

Dumbbell Deadlifts aren’t just another leg exercise. This is a hip hinge exercise, one of the most important movement patterns in your training.

And it lights up more than just your lower body. The Dumbbell Deadlift recruits the entire posterior chain, challenges your grip, builds back muscles top to bottom, and forces your core to stabilize.

To understand why this move deserves a permanent spot in your program, let’s break down each muscle group it hits and how they work together to turn a simple pull into one of the most complete strength builders you can do.

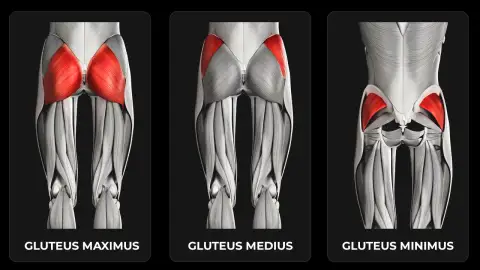

GLUTEUS Maximus

This is the prime mover. The glute max is what drives your hips from flexion back to extension every time you stand tall with the dumbbells.

It’s the muscle that locks out the lift, generates explosive hip power, and builds the shape and strength most people associate with the deadlift.

GLUTEUS MEDIUS

Tucked under the glute max, the glute medius keeps you stable.

Every time you hinge down with two dumbbells or even more so during Single-Leg Deadlifts or a Suitcase Deadlift, it prevents your hips from shifting side to side.

It doesn’t just abduct the hip. It keeps your pelvis level so the bigger movers can fire effectively.

GLUTEUS MINIMUS

The smallest of the trio, the glute minimus acts like a stabilizer deep under the surface.

Along with the medius, it helps control hip rotation and abduction, keeping your knees tracking properly and your pelvis steady.

It may not be the star of the show, but without it, you’d wobble and leak strength with every rep.

Together, the glute max, medius, and minimus form the foundation of the dumbbell deadlift.

The max powers the hip hinge, while the medius and minimus make sure you stay balanced, controlled, and safe under load.

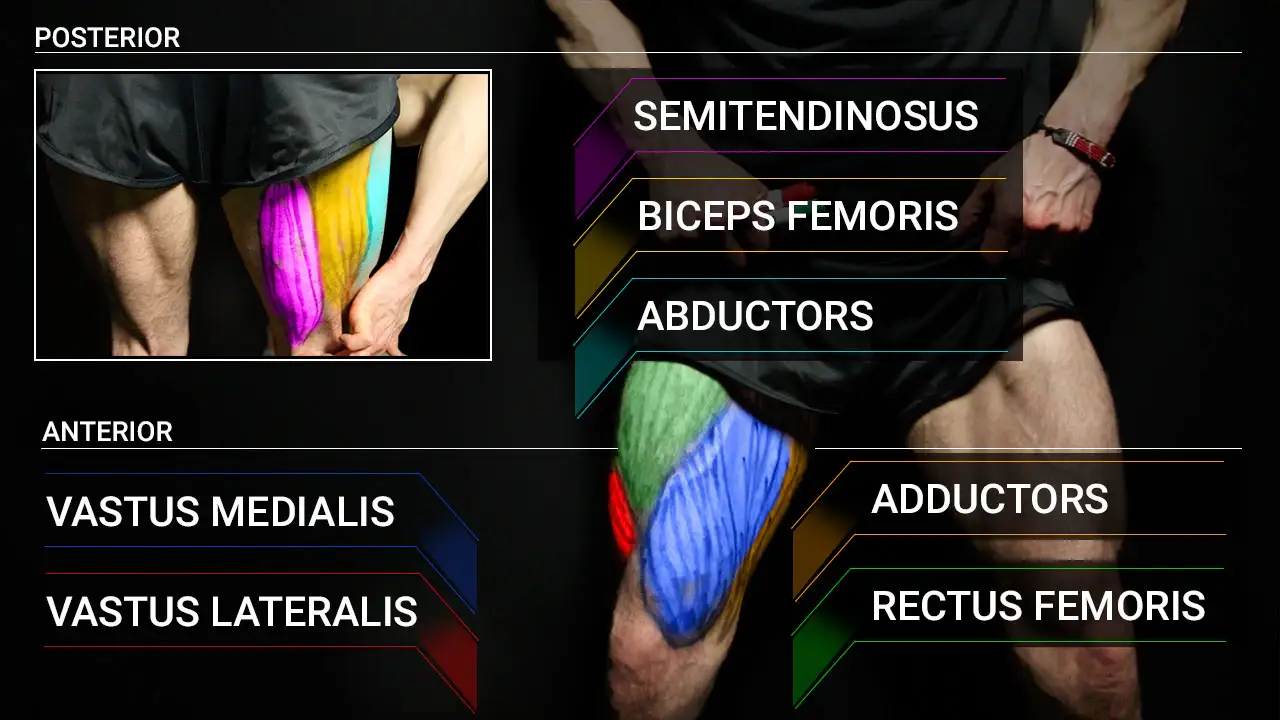

BICEPS FEMORIS

Running along the outside of the back of your thigh, the biceps femoris is the hamstring muscle most responsible for that stretch you feel at the bottom of Romanian Deadlifts or Dumbbell Deadlifts.

Its job is to extend the hip, driving you out of the hinge, and assist in knee flexion.

In the Dumbbell Deadlift, it takes on the brunt of the tension as you resist gravity on the way down.

Strong biceps femoris muscles mean smoother pulls and more power in the lockout.

SEMITENDINOSUS

On the inner side of the hamstring group, the semitendinosus (along with its deeper partner, the semimembranosus) plays the stabilizer role.

These muscles help control hip extension while also keeping your legs aligned under the load.

They share the load with the biceps femoris to bring you back to standing.

Without them, your hip hinge would be unstable, and your knees would drift out of position.

Together, the hamstrings are more than just knee benders.

In a Dumbbell Deadlift, they are the loaded springs that store energy in the descent and release it with power in the ascent, making them one of the most important muscle groups in the entire deadlift movement pattern.

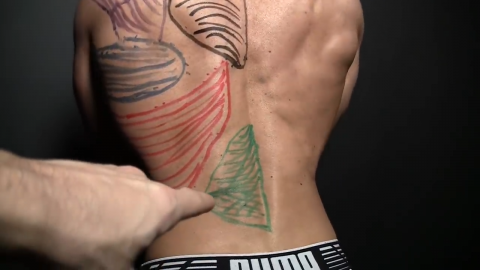

ERECTOR SPINAe (lower back)

The erector spinae are a group of muscles that run vertically along both sides of your spine, from your pelvis all the way up to your neck.

Think of them as the steel cables that keep your torso upright under load.

In the Dumbbell Deadlift, their job is to resist spinal flexion and prevent your back from folding.

Even though the erectors don’t produce much movement during the lift, they’re firing constantly to lock your posture in place.

This is why you’ll often feel a deep burn in the lower back after higher-rep sets. It’s an isometric hold, not a dynamic contraction.

UPPER BACK

While the lower back locks the spine in place, the upper back keeps the chest proud, and the dumbbells close to your body.

This involves several key players: the trapezius, rhomboids, and rear delts. Together, they create a muscular “scaffold” that stops your shoulders from collapsing forward under load.

Every rep of the Dumbbell Deadlift demands scapular retraction, pulling the shoulder blades back and down, and that’s where the upper back muscles shine.

Without this engagement, the dumbbells drift forward, the chest caves, and tension bleeds out of the posterior chain.

A strong upper back doesn’t just protect your spine. It makes you more efficient.

When the traps and rhomboids are dialed in, the dumbbells track tight to your legs, your hip hinge feels smoother, and you can lift more weight safely.

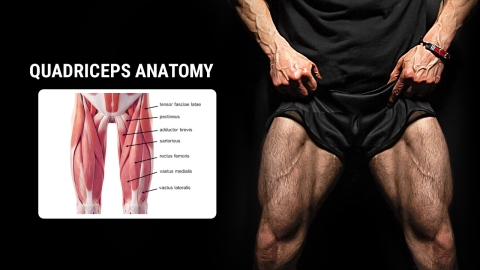

QUADS

The quads don’t dominate this lift like in a Barbell Squat, but don’t mistake them for bystanders.

Positioned on the front of the thigh, the quads (rectus femoris, vastus lateralis, vastus medialis, and vastus intermedius) extend the knee and provide critical support during the first phase of the lift.

When you hinge down to grab the dumbbells, the knees naturally bend slightly. On the way up, the quads work to straighten them, synchronizing with the glutes and hamstrings to drive you back to standing.

Their contribution is smaller compared to a Traditional Squat, but without the quads engaging, you’d have no smooth transition from the bottom of the pull to the lockout.

FOREARMS

Your grip is the handshake between you and the dumbbells and if it fails, the entire lift collapses.

The forearm muscles, including the flexors and extensors that run from the elbow down into the hand, are working nonstop in the dumbbell deadlift.

Unlike machines or straps that take tension off the hands, dumbbells force you to own every ounce of the load.

On the palm side of the forearm, the flexors are firing to clamp your fingers around the dumbbell handles.

Every inch of the descent is an isometric test of endurance as these muscles fight against the pull of gravity.

If your grip strength lags, you’ll feel the dumbbells start to slip long before your glutes or hamstrings give out.

On the opposite side, the extensors stabilize the wrist and prevent it from rolling forward.

A weak wrist position doesn’t just cost you the lift. It creates an energy leak that ripples up the chain, destabilizing the entire hip hinge.

A locked, neutral wrist ensures the load transfers cleanly from your hands into your posterior chain.

CORE (ABS & OBLIQUES)

The rectus abdominis, the six-pack muscle everyone trains for looks, has a much bigger job here.

Instead of crunching your torso forward, it’s resisting extension and flexion forces during the hip hinge.

Think of it like cinching a strap around your midsection. A tight, braced core keeps the lumbar spine neutral as you lower the dumbbells and rise back up.

In high-rep sets, this is often the first area to give out, which is why many lifters “fold” under fatigue.

The internal and external obliques wrap around the sides of your torso like armor.

During the Dumbbell Deadlift, they stabilize against rotation and lateral flexion.

Strong obliques don’t just protect the spine. They make every rep tighter, straighter, and more efficient.

DUMBBELL DEADLIFTS VS. BARBELL DEADLIFTS

Ask most lifters what a Traditional Deadlift looks like, and they’ll point straight to a barbell.

Conventional deadlifts, sumo pulls, and heavy singles are the standard. But the Dumbbell Deadlift brings something different to your workouts.

It changes the way you hinge, alters the stress on your spine, and opens up movement patterns a barbell simply can’t replicate.

Before you decide which variation belongs in your program, you need to know the real differences in range of motion, loading potential, grip demands, and overall carryover.

RANGE OF MOTION

Dumbbells give you freedom of movement that a barbell can’t.

Because the weights sit at your sides instead of in front, you can hinge deeper, if your mobility allows it, placing more stretch on the hamstrings and glutes.

That extra range makes Dumbbell Deadlifts and their variations, especially valuable for targeting weak links in the posterior chain.

LOADING POTENTIAL

The barbell wins when it comes to absolute load.

If you’re chasing max strength, conventional or Sumo Deadlifts with a barbell will always allow heavier weights.

But accessibility matters.

Not everyone has a barbell and plates at home, and not everyone needs to pull 400 pounds to see results.

Dumbbells are easier to set up, easier to progress, and far more versatile when it comes to cycling through different deadlift movement patterns.

GRIP & CONTROL

With a barbell, your grip is fixed. With dumbbells, every rep is a test of control.

Your forearms and grip endurance are pushed harder, especially in unilateral lifts like the Suitcase Deadlift or Single-Leg Deadlift.

Even dynamic patterns like a Dumbbell Deadlift to Press force you to stabilize each hand independently.

That extra demand builds real-world strength you don’t always get from a bar locked in place.

SPINAL STRESS

Many lifters find dumbbell deadlifts easier on the lower back.

The neutral hand position keeps the shoulders from internally rotating, and the load sits closer to your center of mass.

That doesn’t mean they’re foolproof (round your spine and you’ll still pay the price) but for athletes with a history of back issues, dumbbells are often a safer entry point into hinge training.

WHO SHOULD CHOOSE WHAT?

So, which should you choose for your fitness goals?

Beginners: Dumbbells first. Easier to learn the hinge, safer for the spine, and flexible enough to train balance and control.

Home Lifters: Dumbbells win again. Minimal space, maximal versatility.

Athletes: Mix both. Barbells build max pulling strength while dumbbells expose asymmetries and reinforce stability.

Powerlifters: The barbell is mandatory for competition, but dumbbells make the perfect accessory work to build the weak links holding back your pull.

HOW TO DO DUMBBELL DEADLIFTS

Most lifters think they know how to deadlift until you hand them a pair of dumbbells. Suddenly the training wheels come off.

With no bar to guide the path and no fixed grip to lock you in, the Dumbbell Deadlift forces you to own the movement.

If your hip hinge is sloppy, if your spine rounds, and if your core isn’t braced, you’ll feel it immediately.

And that’s exactly what makes this version such a powerful teaching tool.

DUMBBELL DEADLIFTS

HOW TO DO THE DUMBBELL DEADLIFT:

- Stand with your feet about hip-width apart.

- Hold the dumbbells in front of your thighs with your palms facing your body.

- Brace your core like you’re about to take a punch, but don’t hold your breath.

- Pull your shoulders back and set your spine neutral from the start.

- Push your hips back, not down. Think of closing a car door with your glutes.

- Keep the dumbbells tight to your body, sliding them down your thighs as you lower.

- Stop when you feel the hamstrings fully lengthen, usually around mid-shin.

- Push through your heels, extend the hips, and stand tall. Squeeze the glutes at the top, but don’t overextend the lower back.

WHAT MAKES IT EFFECTIVE: The Dumbbell Deadlift works because it strips the lift down to its fundamentals. You can’t muscle it with just your quads or arms. If the hip hinge isn’t perfect, the weight won’t move efficiently, and your back will let you know. By keeping the load close to the body and forcing stabilization in both hands, the Dumbbell Deadlift builds glute and hamstring strength, reinforces spinal stability, and carries over to every other hinge pattern, from barbell pulls to athletic power.

DUMBBELL DEADLIFTS: COMMON MISTAKES

The dumbbell deadlift is brutally honest. If your form is even slightly off, you’ll know it, usually in the form of wasted reps, lost tension, or an angry lower back.

The problem is that most lifters keep repeating the same mistakes and never fix them.

Let’s break down the biggest errors and the exact fixes to make sure your dumbbell deadlifts build strength instead of breaking you down.

ROUNDING THE LOWER BACK

Rounding turns the dumbbell deadlift into a spine-flexion exercise and that’s not the goal.

When the erector spinae can’t hold the line, the load shifts to the passive structures of the spine: ligaments, discs, and connective tissue.

Over time, that’s where injuries happen.

Most lifters round because they lose their brace or chase depth they don’t have mobility for.

Brace your core before you hinge. Think of locking your ribs down and tightening as if someone’s about to hit you in the gut. Pull the shoulders back, engage the lats, and set a neutral spine.

If mobility is the issue, stop at mid-shin instead of forcing the dumbbells to the floor.

SQUATTING INSTEAD OF HINGING

If your knees are dropping forward and your hips are lowering straight down, you’ve stopped doing a deadlift and started doing a bad squat with dumbbells in your hands.

That takes the emphasis away from the posterior chain (glutes and hamstrings) and dumps it onto the quads, completely defeating the purpose of the hip hinge.

Lead the movement with your hips, not your knees. Push the glutes back as if you’re closing a car door behind you.

Keep only a soft bend in the knees and lock that angle in place while the hips travel backward.

You should feel a stretch in the hamstrings, not a burn in the quads. If you don’t, reset and try again.

LETTING THE DUMBBELLS DRIFT FORWARD

The farther the dumbbells move from your center of mass, the heavier they become on your spine.

Even 40-pound dumbbells can feel like double when they drift forward.

This mistake usually happens when the upper back isn’t engaged, the lats aren’t pulling tight, or fatigue causes the arms to swing away from the body.

Treat the dumbbells like they’re on rails, sliding straight up and down your thighs and shins.

Before every rep, set your lats by pulling the shoulders down and back.

Imagine trying to squeeze oranges in your armpits and hold them there as you hinge. The dumbbells should never leave your body’s midline.

OVEREXTENDING AT THE TOP

A good deadlift ends when your hips are locked out. But a lot of lifters drive past neutral, arching the lower back and throwing the ribcage forward.

This isn’t extra credit. It’s extra stress on the lumbar spine with zero benefit to muscle growth.

Overextending doesn’t build stronger glutes. It just wrecks your back.

Stand tall, don’t lean back. The end of the lift is when your hips and shoulders are stacked directly over your feet.

Think of squeezing the glutes hard at the top, not cranking the spine into extension. If you catch yourself leaning, reset, lighten the weight, and focus on finishing tall instead of finishing bent.

USING TOO MUCH WEIGHT TOO SOON

Ego lifting with dumbbells doesn’t just look bad. It breaks down your form faster than anything else.

Because each arm has to stabilize independently, the Dumbbell Deadlift punishes sloppy control more than a barbell.

Go too heavy too fast and your hinge collapses, the dumbbells drift, and your reps turn into a mess.

Earn the right to go heavy. Start with a load you can dominate for 8–12 clean reps.

Once you’ve locked in the hinge and can maintain posture from the first rep to the last, then start pushing the weight.

Remember that the Dumbbell Deadlift is only effective if your form holds. If your spine rounds or the dumbbells swing, you’re not building strength. You’re practicing bad habits under load.

HOW TO PROGRAM DUMBBELL DEADLIFTS

The Dumbbell Deadlift isn’t just a placeholder for people without a barbell. How you program it determines what you get out of it.

Done right, it can be a primary strength-builder, a muscle-building accessory, or a conditioning tool.

The key is knowing where it belongs in your week and how to adjust the reps and sets for your goal.

AS A MAIN LIFT

If you train at home or don’t have access to a barbell, the Dumbbell Deadlift becomes your main hinge.

It can still build a thick posterior chain, challenge your core, and develop grip strength in ways a barbell won’t.

Use it early in your workout while you’re fresh so you can push load and intensity.

Focus on progressive overload by slowly increasing dumbbell weight, extending range of motion, or adding tempo work (like a slow eccentric).

AS AN ACCESSORY

If the Barbell Deadlift is already in your program, dumbbells fill the gaps.

Barbell pulls build max strength, but dumbbells highlight weaknesses such as imbalances between sides, instability in the hinge, or poor grip endurance.

Romanian Dumbbell Deadlifts work perfectly after heavy barbell sets to build hamstring hypertrophy.

Single-Leg Deadlifts and Suitcase Deadlifts target stabilization and force your core to stay engaged.

Treat these as accessory lifts in the mid-to-late part of your workout.

REP RANGES AND GOALS

How you program the dumbbell deadlift changes what you get out of it.

The same exercise can build max strength, pack on muscle, or push endurance, if you know how to adjust the reps and loading.

Strength (4–6 reps): Use the heaviest dumbbells you can handle with perfect hinge mechanics. Think low reps, multiple sets, long rest.

Hypertrophy (8–12 reps): Moderate weight with strict tempo. Focus on tension with the hamstrings loaded on the way down and glutes locked hard at the top.

Endurance (12–20 reps): Lighter weight, crisp form, minimal rest. Great for conditioning the posterior chain, improving work capacity, and building grip endurance.

The Dumbbell Deadlift isn’t a throwaway lift.

For beginners, it’s the perfect way to learn the hip hinge safely. For advanced lifters, it’s the accessory that fixes weak points holding back your barbell pull.

And for athletes, it’s a versatile tool that builds strength, stability, and endurance without beating up the spine.

Where you place it in your workout should reflect your goals, but no program is complete without it.

Check out our complete line of ATHLEAN-RX Supplements and find the best training program for you based on your fitness level and goals.

- Dumbbell Deadlifts train the full posterior chain, build grip strength and stability that carry over to every lift, and provide a safer entry point for beginners or lifters with back or shoulder issues.

- Dumbbell Deadlifts differ from Barbell Deadlifts because the weights sit at your sides, bringing the load closer to your center of mass and often allowing a greater range of motion.

- They also demand more from your grip, balance, and stability, while the neutral hand position can make them easier on the spine.

- Here’s how to perform the Dumbbell Deadlift:

- Stand with your feet hip-width apart, holding the dumbbells in front of your thighs with your core braced and spine neutral.

- Initiate the movement by hinging at the hips while pushing your glutes back and keeping a soft bend in the knees.

- Keep the dumbbells close to your legs as you lower, stopping when you feel a strong hamstring stretch around mid-shin level.

- Drive through your heels to return to standing, extending the hips, and squeezing the glutes at the top without leaning back.

- Inhale as you lower into the hinge, then exhale forcefully as you drive up to lockout.

DUMBBELL DEADLIFT FAQ

Yes, and they’re more effective than most people give them credit for.

Dumbbell Deadlifts train the same key players as the barbell deadlift: glutes, hamstrings, erector spinae, traps, forearms, and core.

The difference is in how the load is applied. With dumbbells at your sides instead of in front, you can often achieve a deeper range of motion, improve stability, and train grip strength more directly.

They’re also more joint-friendly. The neutral hand position reduces stress on the shoulders and lower back compared to a barbell locked in front of your shins.

That makes dumbbell deadlifts especially useful for beginners, home lifters, or anyone who has trouble staying pain-free with a barbell.

Are they the best for max strength? No, barbells still reign there. But for muscle development, posterior chain activation, and overall movement quality, dumbbell deadlifts are extremely effective.

Stand with your feet about hip-width apart and dumbbells in front of your thighs.

Brace your core, pull your shoulders back, and lock in a neutral spine.

From there, initiate the movement by pushing your hips back. Don’t drop into a squat. Keep a soft bend in the knees but maintain tension in the hamstrings.

Lower the dumbbells by sliding them down your thighs, keeping them close to your body. Stop when you feel a full hamstring stretch or when the dumbbells reach mid-shin.

To stand up, drive through your heels, extend the hips, and squeeze the glutes at the top without leaning back.

Both are valuable, but they’re not interchangeable.

The Dumbbell Deadlift is a ground-up pull. You hinge at the hips and bend at the knees enough to get the dumbbells to the floor or mid-shin. Both the glutes and quads share responsibility in driving you back to standing.

The Romanian Deadlift (RDL), on the other hand, starts from the top and keeps the knees only slightly bent. The movement is almost entirely a hip hinge, and the goal is to load the hamstrings under maximum stretch. It doesn’t use the same level of quad involvement, and you never reset the dumbbells on the ground between reps.

Absolutely. A compound lift is defined by multiple joints and muscle groups working at the same time and the Dumbbell Deadlift is a textbook example.

Your hips extend, your knees extend, your core stabilizes, and your upper back locks in. That makes it a total body movement that builds both strength and coordination.

This is what separates it from isolation lifts like Leg Curls or Leg Extensions. The Dumbbell Deadlift demands that your entire body work as a unit.

That’s why it has such great carryover to athletic performance, Barbell Deadlifts, and even everyday tasks like lifting groceries or moving furniture.

The more compound movements you master, the more bang for your buck you get in training. And the Dumbbell Deadlift is one of the best compound pulls you can do when equipment or space is limited.

Jeff Cavaliere M.S.P.T, CSCS

Jeff Cavaliere is a Physical Therapist, Strength Coach and creator of the ATHLEAN-X Training Programs and ATHLEAN-Rx Supplements. He has a Masters in Physical Therapy (MSPT) and has worked as Head Physical Therapist for the New York Mets, as well as training many elite professional athletes in Major League Baseball, NFL, MMA and professional wrestling. His programs produce “next level” achievements in muscle size, strength and performance for professional athletes and anyone looking to build a muscular athletic physique.